By Carla Crowder, Alabama Appleseed Executive Director

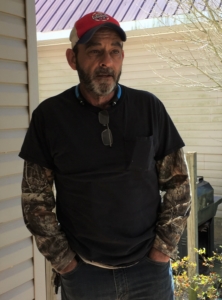

Antonio was incarcerated at St. Clair prison a few years ago when another prisoner bit off part of his ear. They were housed in a dorm that supposedly offered rehabilitative services. For Antonio, permanent disfigurement was the outcome.

Incarcerated people in Alabama are routinely subjected to violence and inhumane conditions in Alabama prisons, according to the U.S. Justice Department.

He did not seek revenge against the man who bit his ear. He redoubled his efforts to engage in what meager positive programming was available at ADOC. He earned his parole. Supported by a devoted mother and sister, he is safely living back in the community.

Antonio was my client during the time I worked on prison conditions litigation at the Equal Justice Initiative before joining Appleseed. Only through the bravery of incarcerated people like him who share the truth of what’s happening inside with the outside world — often at great risk to their safety — can desperately needed change occur.

His situation came to mind this week as I read through the U.S. Department of Justice’s 56-page report about its investigation into the Alabama Department of Corrections. It documents horrific violence and a culture of corruption, mismanagement and indifference. DOJ found an “enormous breadth of Eighth Amendment violations.” In plain terms, the State of Alabama is breaking the law, knows it’s breaking the law, and has been doing so for a long time.

St. Clair Correctional Facility, where the Alabama Department of Corrections promised a federal court it would improve security, but did not make good on that promise.

Individuals who break the law hear a lot about reform, about accepting responsibility for their actions. They are told they must change their ways and not recidivate. If they commit crimes over and over, the penalties increase under Alabama’s Habitual Felony Offender Law.

Antonio understood that.

But the government that incarcerated him in conditions that resulted in permanent harm to his body has not stopped breaking the law, despite decades of harm imposed on the Alabamians in their custody. The United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division and all three U.S. Attorney’s Offices in Alabama, working under a Justice Department led by former Alabama Attorney General and Senator Jeff Sessions for much of their investigation, concluded scathingly: “ADOC has long been aware that conditions within its prisons present an objectively substantial risk to prisoners. Yet little has changed.”

The timeline stretches back to the Wallace era. As early as 1975, a federal court stopped ADOC from accepting any new prisoners into four of its prisons until the population of each was reduced. Again in 2002, a court order declared dangerous crowding and understaffing at Tutwiler Prison for Women to be in violation of the Eighth Amendment. In 2011, another federal court found ADOC facilities understaffed and overcrowded. In 2014, DOJ documented rampant sexual abuse by staff of women at Tutwiler. Later in 2014, EJI urged the state to investigate and address homicides at St. Clair prison and filed a lawsuit alleging unconstitutional violence and abuse there.

And now, as documented by a two-and-a-half year federal investigation, so many people die in state prison custody that the ADOC lost count and classified some homicides as natural deaths.

“Alabama does not have a reliable system for tracking the deaths that occur within its custody,” the DOJ found. Consider the grim irony of that fact. Our state punishes people who commit acts of violence — and many with convictions for drug use or property crime — through a prison system unable and unwilling to keep track of who dies there and how.

To people numbed to bad news by the steady flow of reports of murders, suicides, and strikes, and violence in our state prisons, this could seem like just another report about the persistent crisis plaguing the Department of Corrections. But it is not. The DOJ laid out five pages of corrective actions expected from the state with strict timelines for implementation. The report is actually a notice to the state, as required by CRIPA (the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act), that the federal investigation found numerous constitutional violations and the ADOC has 49 days to begin addressing the problems or be sued by the federal government.

Alabama’s elected leaders have attempted to address this crisis before. Multiple task forces have tweaked sentencing laws and parole policies, and “the violence has only increased,” the DOJ found. Meanwhile, Alabama has maintained the country’s fifth-highest incarceration rate for decades. That also means we have the fifth highest incarceration rate in the world, if every U.S. state were a country, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Alabama cannot build its way out of this problem, nor can it buy its way out. Our elected leaders must finally acknowledge that Alabama’s people are not worse and more deserving of incarceration than nearly every other population on the planet. They must stop relying on the politics of fear, on pressure from the victims’ lobby, and on our entrenched system of policing for profit that places the acquisition of funding for law enforcement above evidence-based public safety.

Antonio, even with his damaged body, turned his life around and changed his ways. Now it’s time for the government that endangered him for a decade to do the same.