(Once you read this, you’ll see why.)

By Libby Rau

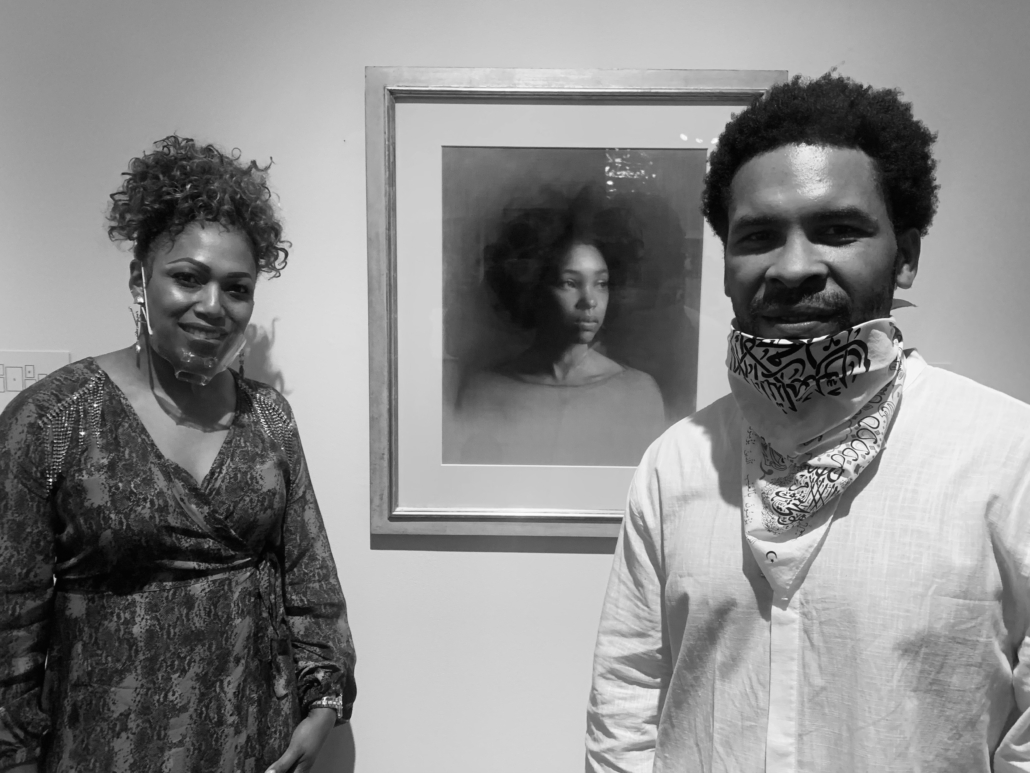

Libby with Michael and his binders full of letters

“Tonight the severity of my sentence has finally started to sink in. …I looked at the law books on my floor and this thought came to me: ‘I’m only pacifying myself.’ I truly don’t know if I can take any more negative encounters with the courts. I keep asking myself, ‘Why me?’ I’m 28 years old. …I know I have to be punished by the law, but it’s inhumane never to be released from prison, especially when no one was hurt….”

In early September of last year, I found myself plopped down at a desk in Appleseed’s Birmingham office, reading these words off yellowed paper. It was the first day of my internship, four giant binders were stacked in front of me, and I’d just been given my first task: begin to read through 36 years’ worth of letter correspondence between Appleseed client Michael Schumacher and his Texan pen-pal, Gene.

Of the thousand-plus letters I would read over the next seven months, these words from a letter that first day would remain some of the most impactful, desperation drenching their every syllable. Michael had written them while in solitary confinement for defending himself against sexual advances by another incarcerated person. He was five years into a life sentence.

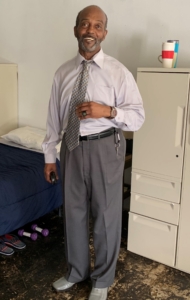

I won’t go into the details of Michael’s story because he’s already written about it here, but the short version is that in 1984, at only 24 years old, he was sentenced to life without parole for his role in a robbery under Alabama’s three strikes law. Despite never physically harming anyone, he was deemed by law and by society to be unworthy of any chance to show he had changed—of any chance to be free. But against all odds, Michael chose redemption for himself and, with Appleseed’s help, was resentenced to time served in 2021 and released after almost four decades in prison.

In his book Just Mercy, Bryan Stevenson talks about the importance of proximity, saying that it was visiting incarcerated individuals in prison that made him realize what career he wanted to have as an attorney. What legal textbooks and analyses could not reveal to him, an incarcerated man singing an old hymn in a prison visiting room did.

While any account–however abbreviated–of Michael’s story is compelling, the details found in the “long version” that I read allowed me a rare proximity to his life in prison that taught me more about Alabama’s legal and prison system than anything else could. I may have known that in 2020 the Department of Justice declared Alabama’s entire prison system for men unconstitutional, in part due to guard-on-prisoner violence, but Michael’s January 5, 1989 letter described to me how a guard broke a nightstick over an incarcerated man’s head, beating him long after he fell unconscious. I may have known that prison is dehumanizing and degrading, but Michael’s experience on March 21, 1990 when he was falsely accused of holding drugs and handcuffed for over 24 hours until he could defecate in a can in front of female guards showed me just how much. I may have known that high security prisons offer the individuals within almost no contact with the natural world, but I didn’t realize the extent of this deprivation until I read in Michael’s October 13, 1999 letter that he touched a leaf for the first time in 15 and a half years. I may have known that life has to somehow go on after being sentenced to die in prison, but I didn’t know the joy that being the prison Scrabble champion and winning “a six-pack of Cokes and bragging rights” could bring until I read Michael’s July 23, 2017 letter.

The point is, proximity like what Michael’s letters gave me changed the way I think about the issues our state faces because they humanized them on a much deeper level. But the power of proximity isn’t just found in words on pages. It’s encountered in everyday, unassuming conversations or observations, and it’s these little (and not so little) interactions that provide the fuel to keep fighting for a better Alabama even when a brighter future seems distant.

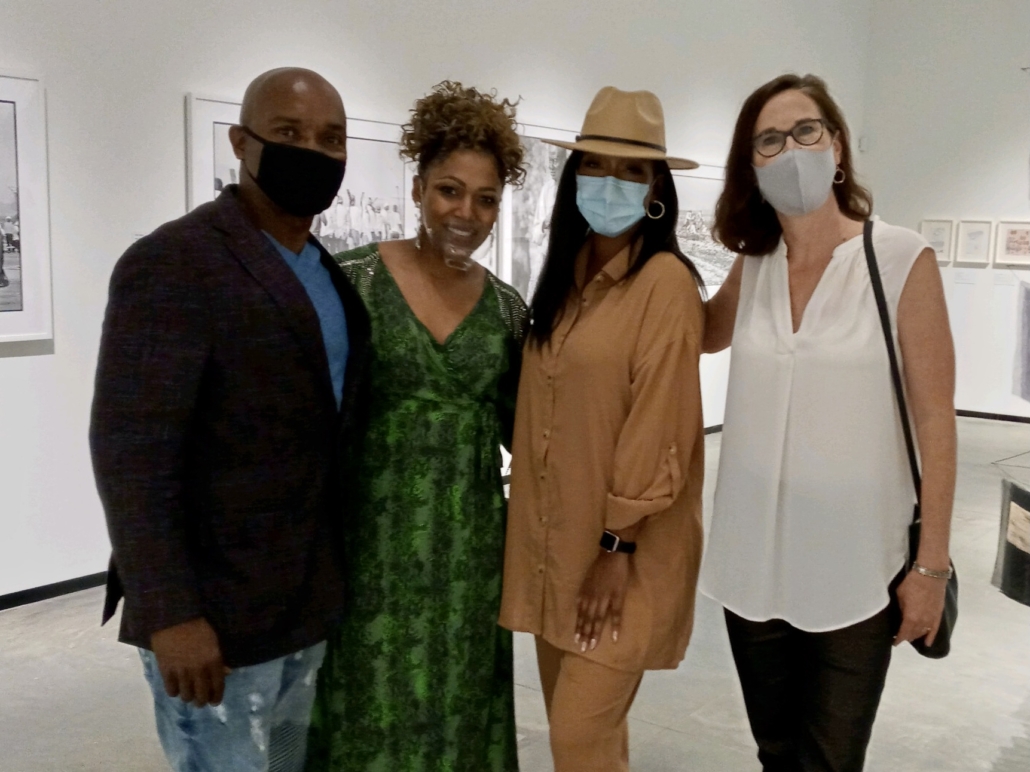

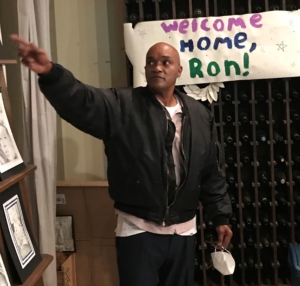

Here are a few of these interactions that stand out from my time as an intern: When Michael was talking about North Carolina’s Grandfather Mountain and was calling it “granddaddy mountain.” The fact that we both have German backgrounds, and comments like “I’m still stuck on the fact that I have family now. That’s just so awesome to me.” The little bag of dried flowers we threw in celebration at his wedding that I kept as a memento and have sitting on my desk. When another Appleseed client, Ron McKeithen, told me about the first time in 37 years he heard the crinkle of fall leaves under his feet. Ron’s contagious smile, and the little note on the index card he wrote me in his beautiful, unique handwriting. How, for a while after his release, he had to remind himself he didn’t have to walk sideways down the stairs anymore–that if he left his back exposed he wouldn’t be stabbed. Our client, Alonzo Hurth’s expression of pure excitement when he walked out of the DMV after passing his driver’s permit test, and the contented smile on his face as he ate his favorite salmon sandwich from a 4th Avenue restaurant where he used to work before his incarceration. The look of disbelief and joy on Joe Bennett’s face as he walked free from Donaldson Prison after 24 years.

And it wasn’t just spending time with clients, it was observing the level of care Appleseed staff put into their work and into those around them, too. It was Carla bringing a fresh apple or other piece of fruit when we would go to a prison to pick up a newly-freed client because she knew that they likely had not had one in years, if not decades. It was Alex planning and setting up Michael and Kathlyn’s wedding on top of already devoting every waking minute of her life to our clients. It was how Callie, our Community Navigator who has her own background of poverty, addiction, loss, and incarceration, sang a hymn as a way of an introduction before giving a talk about her life.

When you are proximate to people and the details of their personalities and stories, you are reminded just how much you have in common–you are reminded of your shared humanity. This is such a simple truth, yet it’s one that is wholly lacking from our systems of prisons and punishment. People are thrown away, out of sight and out of mind, and society is allowed to forget they are human, and they are never really allowed a chance to truly repair the harm done, because punishment is one dimensional and restoration is three dimensional.

I recently had a brief conversation with an Alabama state legislator who expressed the view that empathy and “heart” watered down the “facts” of policy and policy proposals. As if the compassion spurred by others’ suffering is somehow not to be trusted when making laws. As if the more humanized issues were, the less factual they became.

All I know is that my time as an Appleseed intern allowed me to understand the facts and facets of these issues better than I ever had precisely because I was closer to the people. I learned that to get to the heart of the matter is to get to the heart of people–to their stories, to their details. And most of all, I learned that liberation is never only one-way.

I can not thank Appleseed enough for these lessons and experiences. I’m humbled to be able to continue working as a Legal Assistant with an organization founded on centering the people most harmed by Alabama’s unjust and inequitable systems and thereby affirming their humanity in everything they do. Thank you, Appleseed. The work continues.